“Whatever one man is capable of conceiving, other men will be able to achieve” – Jules Verne

After talking ‘organic horsepower’ in the previous article, let’s get back to mechanical horsepower and onto the long path of the history of hydrogen and fuel cells.

As you may know, one-third of all automobiles were battery-powered electric vehicles (EV) – even some hybrid EVs- during the first quarter of the twentieth century. The ‘gas battery’, now known as the fuel cell, had been invented, or more appropriately, discovered, a long time ago. However, not all the pieces of a puzzle do fit together all of the time. Collectively, humans are not really that smart, after all.

The first appearance of Sir William Robert Grove’s ‘gas voltaic battery’ in 1839 produced proof that electricity could be generated with hydrogen and oxygen. But when EVs were relatively plentiful during the first two decades of the twentieth century and well into the 1920s, nobody in the growing automobile industry seemed to remember this. Porsche and other automotive pioneers produced and sold hybrid electric vehicles (HEV) during the early years, but seemingly nobody saw the potential of Grove’s gadget for electric vehicles as a ‘range extender’ for the standard battery.

Grove’s invention was left to linger as just another scientific curiosity because Volt and Ampere meters to perform useful measurements were non-existent. Only now and then, a scientist would come across the idea, and carry on where Grove’s experiments had left off.

Since hydrogen (H2) is the fuel of fuel cells, we ought to look at some early uses of H2 as a fuel in internal combustion engines as well as early applications of fuel cells. As you may be aware, H2 can be extracted from many sources, from coal, petroleum or natural gas, and many other matters. Since the world must get away from the carbon emission of those base stocks, the goal is to produce HY2 from water by electrolysis. The substantial energy required for this process must come from renewable sources, like wind, wave or solar power. These are now being developed along with fuel cells at the beginning of the Hydrogen Age.

In a previous part in this series, I wrote about the activities of Rivaz but skipped Lenoir. Etienne Lenoir patented his two-stroke engine in 1860, and he installed it in a three-wheel wagon, named the “Hippomobile”, because its fuel – hydrogen – was electrolyzed from water. French humor, I guess. (Look for another Hippomobile picture on this website) Lenoir later experimented by running his engine on different fuels, coal gas among them – the very first flex-fuel engine. (Is there absolutely nothing new under the sun? The above picture also has a disk brake of sorts.) Lenoir built and sold almost 400 of these engines, competing successfully with steam engines of the time.

In 1874, science fiction writer Jules Verne predicted that the world would use water as a fuel in the future – he was partly correct. And ‘Dr. Mirabilis’ had already foretold ‘speeding wagons’ in the middle ages. (Other than on the Autobahn, we are being fined for doing that). I ask you; did these people in the old days have nothing else to worry about, but to imagine what might happen in the far future? I am struggling here just to get recent history into a meaningful sequence.

Fifty years after Grove’s experiments, in 1889, Charles Langer and Ludwig Mond, tried to build an apparatus that would function to create electricity with air and coal gas. At about the same time, William White Jaques conducted similar research, using different materials. All three of these scientific experimenters have been credited with being the first to use the term “fuel cell”. (I believe it was one of the bureaucrats in the patent office, who wanted to confuse us). Oh, the vagaries of history.

In a previous part in this series, I wrote about the activities of Rivaz but skipped Lenoir. Etienne Lenoir patented his two-stroke engine in 1860, and he installed it in a three-wheel wagon, named the “Hippomobile”, because its fuel – hydrogen – was electrolyzed from water. French humor, I guess. (Look for another Hippomobile picture on this website) Lenoir later experimented by running his engine on different fuels, coal gas among them – the very first flex-fuel engine. (Is there absolutely nothing new under the sun? The above picture also has a disk brake of sorts.) Lenoir built and sold almost 400 of these engines, competing successfully with steam engines of the time.

In 1874, science fiction writer Jules Verne predicted that the world would use water as a fuel in the future – he was partly correct. And ‘Dr. Mirabilis’ had already foretold ‘speeding wagons’ in the middle ages. (Other than on the Autobahn, we are being fined for doing that). I ask you; did these people in the old days have nothing else to worry about, but to imagine what might happen in the far future? I am struggling here just to get recent history into a meaningful sequence.

Fifty years after Grove’s experiments, in 1889, Charles Langer and Ludwig Mond, tried to build an apparatus that would function to create electricity with air and coal gas. At about the same time, William White Jaques conducted similar research, using different materials. All three of these scientific experimenters have been credited with being the first to use the term “fuel cell”. (I believe it was one of the bureaucrats in the patent office, who wanted to confuse us). Oh, the vagaries of history.

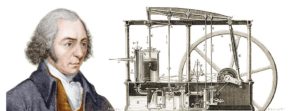

PICTURE: James Watt & steam engine

What’s more, at about this time, the steam engine was occupying the minds, time and resources of most inventors and investors.

Next: Uncertain Times