“True greatness is when your name is like ampere, watt, and diesel — when it’s spelled with a lower case letter.” Richard Hamming

It is also great that new automakers use old pioneers’ names, such as Tesla, Nicola, Faraday — and who next?

It takes many great minds and many years to make a new system or structure commonplace; — Hydrogen-powered cars are here now, but when will you and I no longer drive a vehicle from the ICE age?

You may have noticed that automakers lately list the power of IC engines in kilowatt as well as in horsepower. That takes us to James Watt. I know how many watts a lightbulb has, but most high-school physics has long been forgotten, I must admit. To recap, it was JW, who tried to equate the power of his steam engine to that of a horse. Wikipedia helps with “The term [HP] was adopted in the late 18th century by the Scottish engineer James Watt to compare the output of steam engines with the power of draft horses. It was later expanded to include the output power of other types of piston engines, as well as turbines, electric motors, and other machinery.” HowStuffWorks explains it more accurately.

That is how we adopted ‘Horse-Power’ when steam cars gave way to ‘(electric)Motor-Cars’ and those with an IC engine. As we are returning to electric motor-cars (that includes fuel cell vehicles), carmakers are trying to familiarize us with electric measurement units, including that of battery power. The VW Golf lists power as “170 HP (125 kW)”, while the Chevy Bolt specs show “150 kilowatts (200 HP)”.

Now back to the horses and truly amazing amounts of organic horsepower, accessible everywhere, in every village, in every town and city – a long time ago.

In New York City, during the late nineteenth century, between one hundred and fifty thousand and two hundred thousand horses were pulling wagons to transport everything the population consumed, and all the raw material needed for the products and the freight the inhabitants of New York produced. People were moving from the countryside to areas of commercial and industrial activity by the droves. Horses also pulled the trams that transported the populace between their newly constructed homes and their productive jobs in mushrooming factories. The industrial revolution was in full swing, and the same was happening in cities and towns all across the country, in America and in Europe.

Horses in such vast numbers left a lot of pollution in liquid and solid form on every street they worked and traveled on, potentially attracting rats and insects, and thus spreading diseases. Reports from America’s largest city inform us that up to 2,000 tons of horse manure had to be removed from the city’s streets on a daily basis. — Yes, I searched for and read the reports, and I checked the math.

On the way to a fire circa 1910 with a steam fire pump

“Horses create 772 grams of pollution per kilometre traveled, modern cars only 72.4 grams per kilometre” Quote from Lee Gerhard, AAPG Explorer, February 2001

No wonder then, that one hundred years ago the world welcomed the automobile with open arms as its environmental savior when the news of their invention spread around the globe. Nevertheless, as we know now, a new type of pollution replaced the old type; it merely was not recognized until decades later.

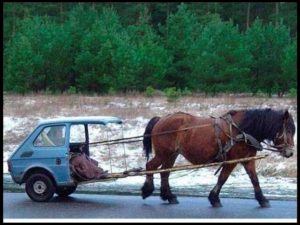

Not a century ago, and not a horse-less carriage, but a transportation method in a developing country. Illustration by Auto Bild.

Cars and trucks were a novelty at first, showing up in small clusters here and there. Then their numbers grew, they were faster than horses and became more reliable as time went on. Naturally, wagon builders, blacksmiths, and veterinarians decried the lack of work and warned that massive unemployment among their ranks would undoubtedly follow.

Does this sound familiar? Remember, all the workers who made radio and television tubes lost their jobs over time when electronic devices were developed. What’s more, all the persons who built carburetors were displaced when fuel injection became the norm in the automotive world more recently. You can surely think of other examples; this is what we consider progress. However, life will always go on and get even better than before, for all those who have been affected. The population keeps increasing, and so will the number of available jobs. Jobs will differ, and they will be created anew as technology changes.

Many of the men and women working in the oil fields now will become unemployed during the next generation when the hydrogen economy takes hold. But who produces hydrogen now? Very few. Education has, and will continue to ready us for the next step. And Mother Nature will provide us with another resource when the old one diminishes.

As one of the above pictures shows, different modes of transport run side by side for a time, and so will vehicles with IC engines and those with hydrogen fuel cells coexist in the near future.

Next: Hopeful times

Again, please note: All pictures are from Google or Wikipedia unless otherwise indicated.