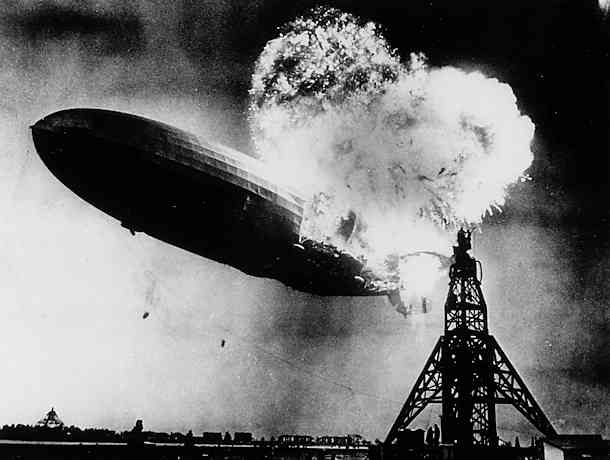

Hindenburg Fallacy & Urban Myth

The Hindenburg zeppelin explosion has long been equated with the dangers of hydrogen. Many who think of hydrogen cars also have the visual in their mind’s eye of the terrible explosion in 1937 in Lakehurst, New Jersey that killed 35 people and left many more injured. But the hydrogen inside the Hindenburg was not the first thing to burn.

|

A NASA research scientist at Cape Canaveral, Addison Bain, has found that the neither the hydrogen nor a bomb in the hull was to blame (the Hindenburg was a gift from Germany’s Third Reich), but rather it was the outer skin of the aircraft that caused the fireball. |

|

This outer canvas had a new protective coating, which was extremely flammable and a single spark of static electricity upon the canvas hull is what sent the Hindenburg to its ruin.

At 803.8 feet in length and 135.1 feet in diameter, the Hindenburg was the largest passenger ship ever to fly. With a massive diameter and length, the Hindenburg would carried a gas volume of 7,062,000 cubic feet. From the very beginning, the Hindenburg was not supposed to carry hydrogen at all. Chairman of Zeppelin, Dr. Hugo Eckner, wished for the Hindenburg to carry the nonflammable gas, helium.

The United States government at that time (and holders of the only natural deposits of helium in the world) were becoming more suspicious of the Nazi government who were funding the zeppelin projects so that massive amounts of leaflet propaganda could be dropped from the airships. The U. S. Government denied Dr. Eckner’s request for helium, so he had to choose hydrogen as an alternative gas or risk losing his fleet and his business altogether.

Dr. Eckner did have an eye for safety, however, as the rooms of the dirigible were made with anti-chamber airlocks and lined with asbestos. Lighters and matches were removed from passengers before the flight and locked away.

Bain believes, though, that the real cause of the explosion was the doping compound used to waterproof and stretch the canvas. Bain has stated that a layer of iron oxide covered with coats of cellulose butyrate acetate mixed with powdered aluminum, was responsible and this same compound is very similar to a mixture used to power solid fuel rockets.

Its needless to say that today’s hydrogen cars and particular the tanks will manufactured with much higher safety standards than the Hindeburg had to face. The H2 vehicle manufacturers already know they have a public relations problem from the get-go concerning the Hindenburg urban myth that must be overcome and comparisons to the older Ford Pinto, while quite natural, will also need to be dealt with accordingly.

With the many years of technical advancements, however, and increasingly sophisticated safety standards, there will be no Hindeburg’s on the road, only H2 cars and other vehicles that have met the highest of government and independent safety standards. And that’s a fact.

Written by Hydro Kevin Kantola